Consumption, known today as tuberculosis (TB), has been one of the biggest killers throughout history. Earliest references date back to the ancient Greeks. They named the disease of the lungs phthisis or consumption; owing to the rapid weight loss that appeared to consume the individual as the disease progressed.

Consumption, known today as tuberculosis (TB), has been one of the biggest killers throughout history. Earliest references date back to the ancient Greeks. They named the disease of the lungs phthisis or consumption; owing to the rapid weight loss that appeared to consume the individual as the disease progressed.

During the time of Hippocrates (460-370 BC), it is believed that consumption was the most widespread disease of the age. There were no treatments; Hippocrates is reported to have instructed his students not to treat patients in the late stages of the disease. Patients were sure to die and it would ruin their reputations as healers.

Typically, but not exclusively, consumption is a disease of the lungs. If left untreated, symptoms include fatigue, night sweats, and a general “wasting away” of the victim; as well as a persistent coughing up of thick white phlegm or sometimes blood.

As the most feared disease in the world, consumption was also called the ‘Great White Plague’ or the ‘White Death’; due to the extreme paleness of those affected. It was also given names that evoked the despair and horror of the condition; such as ‘Robber of Youth’, ‘Captain of all these men of Death’, ‘Graveyard Cough’, and ‘King’s-Evil’. The disease was known to strike down the young and old, the rich and poor, without discrimination.

Whether it is known as Consumption, lupus vulgaris (TB of the skin) or Pott’s disease (TB of the bones), TB is one of history’s great killers.

Consumption has Claimed the Lives of Over One Billion People

Consumption has been a scourge throughout history and may have killed more people than any other microbial pathogen. Current estimates suggest approximately 1 billion people around the world have succumbed to consumption in the past two centuries alone.

Today we know tuberculosis is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. At the beginning of the 19th century, physicians were still in doubt as to whether it was an infectious disease, a hereditary condition or a type of cancer. Indeed, it was only in 1865 that a French military doctor demonstrated that the disease could be passed from humans to cattle, and from cattle to rabbits. This was a remarkable breakthrough. Until this time, the medical theory held that each case of consumption arose spontaneously in predisposed people.

In the UK and Europe, consumption caused widespread public concern during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was seen as an endemic disease of the urban poor. By 1815 it was the cause of one in four deaths in England. Up from 20% in 17th century London. In Europe, rates of tuberculosis began to rise; in the early 1600s and peaked in the 1800s when it also accounted for nearly 25% of all deaths.

Between 1851 and 1910 in England and Wales four million died from consumption. More than one-third of those fatalities were aged 15 to 34; half of those aged 20 to 24, giving Consumption the name the robber of youth.

A Disease of the Poor

When a person is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, they are unlikely to display any immediate symptoms. Patients with a healthy immune system, good nutrition and clean air are often able to overcome the disease. Even without treatment, approximately 20% of those who contract the disease can make a full recovery.

Consumption, however, was closely linked to both overcrowding and malnutrition making it one of the principal diseases of poverty. In the 19th century, many of the lower classes lived in crowded, unsanitary conditions. With weakened immune systems brought on by poor nutrition and ill health, it is easy to see how an untreatable condition such as consumption could take hold. In 1838 and 1839, in England, between a quarter and a third of tradesmen and labourers died from tuberculosis. The figure was approximately one-sixth in “gentlemen”.

Wealthy tuberculosis sufferers could afford to travel in search of sunny and mild climates. Poorer people had to look after their own ill consumptive family. Often in dark, unventilated rooms, they sealed their own fate to die of the same disease a few years later.

When being a Close-Knit Family was Bad for your Health

Although M. tuberculosis is contagious, it’s not easy to catch. It is spread through the air when people with active TB in their lungs cough, spit, speak or sneeze. Each action can expel infectious aerosol droplets, 0.5 to 5.0 µm in diameter. A single sneeze can release up to 40,000 droplets, each one of which may transmit the disease.

Those who have prolonged, frequent or close contact with the consumptive patient are at most risk of becoming infected. People are more likely to contract the disease from a family member than from a stranger.

The probability of transmission from one person to another depends upon several factors. These include the number of infectious droplets expelled by the carrier, the effectiveness of ventilation, the duration of exposure, the virulence of the M. tuberculosis strain, and the level of immunity in the uninfected person.

A Disease that Consumes

In the early stages of the disease, when people show no signs of symptoms, the disease is said to be latent. At this point, individuals are not contagious. Over time, however, if the disease is allowed to become active, people develop symptoms and become contagious. The transformation of latent to active disease can take as little as a few weeks, or it might occur years later.

Overall, about half of those people who develop the active disease will do so within the first two years of infection. The duration of active tuberculosis from onset to cure or death is approximately three years.

Common symptoms would include chest pain, fever, night sweats, severe weight loss, a prolonged cough producing sputum or occasionally, blood. In many people, consumption was characterised by a time of symptoms, interspersed with periods of remission.

The Look of Vampires

Consumption was so prevalent in the 19th century that it played a large role in literature, art and opera. It became romanticised in society by poets such as Keats, Shelley and Byron. Writers such as Edgar Allan Poe, Robert Louis Stevenson and Emily Brontë also romanticised the disease. Ironically, many of these names ultimately succumbed to the disease themselves. In some situations, the deaths of characters were portrayed as romantic, despite being anything but glamorous.

In addition to the symptoms described above, consumptive patients often took on a thin, pale, melancholy appearance that some found attractive. Byron once remarked to his friend, Lord Sligo, “I should like, I think, to die of consumption.” When Lord Sligo asked why, Byron replied, “Because then all the women would say ‘See that poor Byron – how interesting he looks in dying.”

John Keats wrote in 1819, “Youth grows pale, and spectre thin, and dies.”

Edgar Allan Poe described his young wife as being ‘delicately, morbidly angelic’ as she lay dying of consumption.

Emily Brontë described the tuberculous heroine in Wuthering Heights as “rather thin, but young and fresh-complexioned and her eyes sparkled like diamonds”.

The imagery of the consumptive was also used in the 19th century to describe the look of vampires and their victims. Consequently, it was sometimes thought that people suffering from the symptoms of tuberculosis, were the victims of vampires or, indeed, were vampires themselves.

The Culprit Identified

During the 19th century, there were no reliable treatments for tuberculosis. Some physicians prescribed bleedings and purgings (with emetics or enemas). Most often, however, doctors could only advise their patients to rest, eat well, and exercise outdoors. Very few recovered. Those who survived their first bout of the disease were haunted by severe recurrences that destroyed any hope for an active life.

Physicians recognised the benefits of breathing clean air. Patients were sometimes moved to mountainous areas in the hope they would be cured. In the early days, however, cures were seldom seen.

The first recorded treatment for consumption was developed in the early 19th century. English physician James Carson demonstrated that injecting air into the pleural cavity could collapse a lung and permit it to heal. The practice, however, seems to have been ahead of its time and was not initially adopted.

The first widely practiced treatment for consumption was to exile patients to the sanatorium. The first sanatorium was opened in 1859 in Görbersdorf, Silesia. After a student with consumption, Hermann Bremer, was told by his doctor to find a healthier climate. When a trip to the Himalayas cured his disease, he returned to Germany and studied medicine before he opened an in-patient hospital in Gorbersdorf. Surrounded by fir trees, the hospital plied patients with good nutrition and exposed them to continuous fresh air. Ultimately, this became the model for all subsequent sanatoria, even into the twentieth century.

The practice of collapsing of the lung finally became standard treatment in 1882. The affected lung would be collapsed, allowing it to “rest” and heal. As it did not work for late stages of the disease, however, it’s usefulness was limited.

Hope for a Cure

On 24 March 1882 the bacillus causing tuberculosis, M. tuberculosis, was finally identified and described by Robert Koch. A discovery he later received the Nobel Prize for in physiology or medicine.

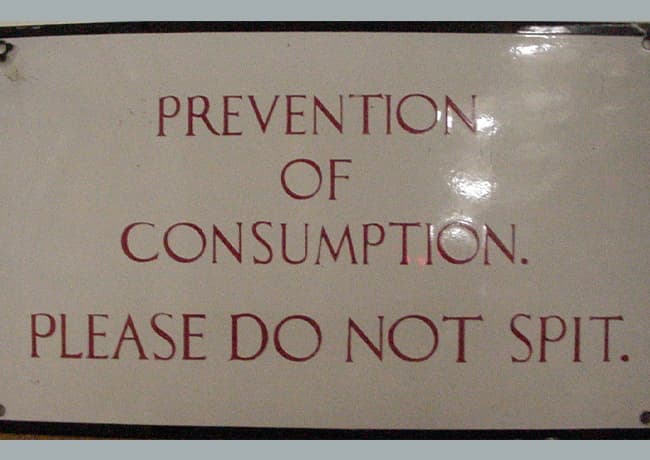

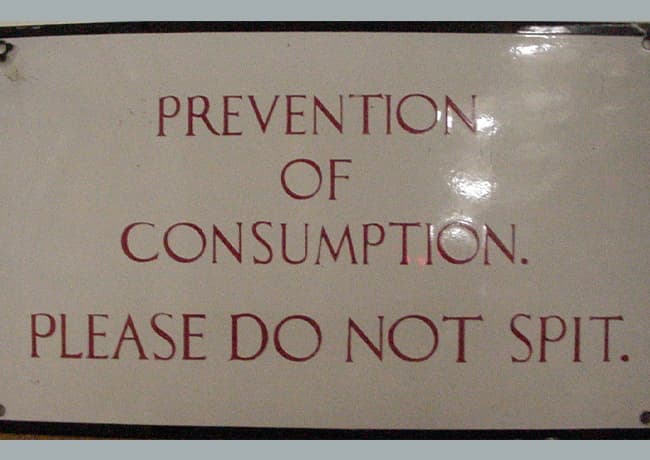

The discovery was greeted with a great deal of excitement. It meant that, for the first time, medicine could finally work toward a cure. It also meant that physicians knew the disease needed to be contained. Almost immediately, it was put on a notifiable disease list in Britain. Campaigns began to stop people from spitting in public places. Infected patients were encouraged to enter sanatoria, often remaining there for months or sometimes years.

Those with money went to the best institutions and received excellent care and constant medical attention. For the infected poor, however, the sanatoria were less satisfactory. They had plainer food and a regime where the patients had to work and do their own housekeeping. For those who still could not afford the sanatorium, improvisations were made at home, which often saw patients sleeping outside.

These measures alone lead to a great improvement in the outcomes of patients with consumption. In England and Wales, between 1860 and 1895, there was a reduction in deaths from consumption of 39%.

In terms of medical treatment, by 1890, Koch had developed a glycerine extract of the tubercle bacilli, “tuberculin”, which he hailed as a remedy. Although it turned out to be ineffective, it did help in the development of a screening test for the presence of pre-symptomatic tuberculosis.

It wasn’t until halfway through the 20th century, in 1946, that the development of the antibiotic streptomycin finally made the effective treatment and cure of TB a reality.

This information was gathered as part of the research for the Ambition & Destiny series. Click here to find out more.

References

- American Lung Association: How we conquered Consumption

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention

- Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health Vol 22. No 2 Part 1

- Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health Vol 22. No 2 Part 2

- Mayo Clinic: Tuberculosis

- Natural History of Tuberculosis 2011; 6(4): e17601.

- Sanatoria and Special Hospitals for the Poor Consumptive and Persons with Slight Means. James M. Anders Trans Am Climatol Assoc. 1898; 14: 154–178.

- The Timeline

- The American Lung Association Crusade

- Today I found Out

- Wikipedia