Despite the need for poor relief, people were desperate to stay out of the workhouse

Provision of aid to the poor has been a problem since the beginning of time. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a tax was placed on land and buildings and the proceeds used to support the poor of the respective parish. Relief was given either in the form of outdoor relief, which provided payments for things such as food and clothing; or as indoor relief in the form of the workhouse.

Outdoor relief was principally given to the able-bodied poor to allow them to remain at home and seek work as and when it became available. Indoor relief was intended for those who were unable to look after themselves such as orphaned children, the sick or elderly.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, however, there was significant pressure on the system and a widely held belief that it was being abused. There were questions over the distribution of money to those who were fit and able to work (able-bodied poor). It was argued that if men were able to work, they should do just that. Many also objected to the allowance provided for children, believing it would encourage paupers to have large families.

Poor Relief in the 19th Century

During the early nineteenth century, with the cost of relief spiraling, a new system was desired to reduce the amount of money spent. This led to the Poor Law Amendment Act, which was passed in 1834. The Act covered England and Wales and by setting out the principles of social policy for the rest of the century, it essentially dictated attitudes towards poverty that dominated public perceptions for the rest of the century.

Finding the money locally to provide for the poor was a continuing problem, but the new Act continued to rely on the parish rate to pay for poor relief. It also supported the importance of local administration. The fundamental change from the earlier legislation was to the way the relief was administered.

In an attempt to reduce the costs, a principal aim of the new Act was to eliminate the distribution of outdoor relief and make the workhouse the centre of all assistance. A Board of Guardians was elected locally to manage the day to day running of the workhouse. In the early years of the Act, men from the landed gentry and aristocrats dominated these positions. Over time, because they wielded great local powers, these men became very influential both locally and politically.

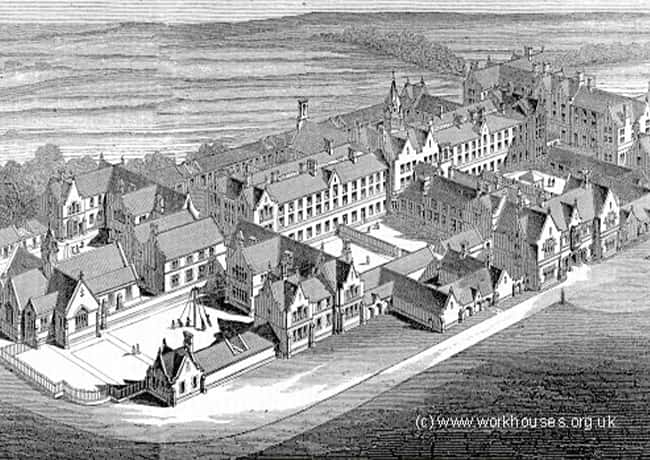

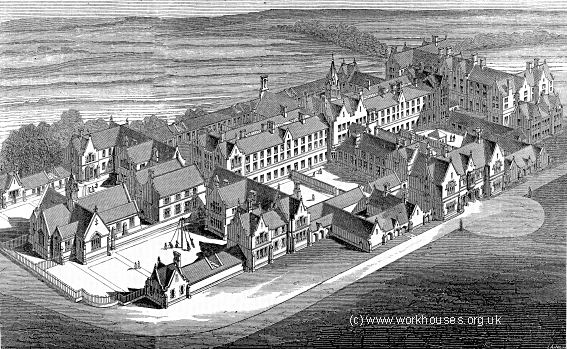

In order to deter people from seeking accommodation, workhouses were intentionally designed to offer a worse standard of living than the lowest living standards of an independent labourer; one of the lowliest occupations available. The idea was that if conditions were so bad, those paupers who had previously claimed outdoor relief because they were work-shy, would choose work rather than enter the workhouse. This would, therefore, reduce costs, as fewer people asked for aid.

The implementation of the Act did not run smoothly, however, and many protests were held across the country against the restriction of outdoor relief. There were many protests in rural areas where it was argued that due to the changing seasons and fluctuations of harvests there were often times when men couldn’t work. Similarly, in the industrial north, the new legislation was felt to be unsuitable for the patterns of work required.

The Legislation Updated

In an effort to retake control of the situation, new regulations were issued in August 1837. Although they repeated the ban on outdoor relief to able-bodied men and women, they did allow exceptions. These were based on policies that were being brought into practice across the country. Exceptions to the ban on outdoor relief included:

- cases of sudden and urgent necessity

- sickness, whereby an able-bodied person was unable to work

- a lack of available workhouse accommodation

- widows

- able-bodied labourers who married before 1834, although their children might be admitted to the workhouse

Widows – A Special Case for Poor Relief

As a woman no longer under the guardianship of her husband or father, the Victorian widow held a unique position. For those whose husbands had left them money, it meant social and economic independence that few other women experienced.

For those whose husbands had little financial worth, or who left their money elsewhere, however, independence often meant they were destitute. Indeed, official records show that a high proportion of women, including widows, were forced to rely on poor relief.

Due to their special circumstances, the Act allowed widows with children to continue claiming outdoor relief. This could be in the form of money, medical services, food or clothes. Outdoor relief could also be claimed by childless widows although in some southern areas relief was later restricted to the first six months of widowhood.

Receiving outdoor relief didn’t mean that these widows were well provided for, however. On the contrary, relief was often insufficient and in order to claim it, women had to ‘settle’ in the place of their husband’s birth. Often this involved transporting women away from their own families, possibly to areas they had never visited, and where they had no friends or support.

As time progressed, churches and charities came to play an important role in supporting widows. During the 1840s and 1850s, for example, it wasn’t uncommon to have sermons preached, and leaflets distributed, that alerted congregations to the plight of widows alongside suffering orphans.

Despite everything, for widows as well as other paupers, one of the most important forms of support came from family and the local community. This was seen particularly in working-class neighbourhoods. Help could take many forms such as taking in lodgers, lending money or goods, handing down clothes, washing clothes for those unable to do their own. There were even local pawn shops or money lenders to help people out until they received some money.

In many cases, these acts of kindness helped people avoid the stigma of the workhouse or even the final indignity of a pauper funeral.

Local Administration, Local Rules

The system of distributing aid locally meant that rules applied in one union were not necessarily copied in others; indeed there were areas that were held up as good and bad examples on how relief should be administered.

For example, poor relief in Birmingham was organised long before the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act. The first workhouse was built in Lichfield Street in 1733 and remained under vestry control until 1783 when Birmingham secured it’s own Act. This allowed ratepayers to elect 108 guardians of the poor.

Because Birmingham already had a workhouse and guardians, it was exempt from most of the provisions of the 1834 Act. Locals were fortunate in that it had a good reputation for things such as dispensary relief and the treatment of pauper children. A report from 1834, however, stated that many parts of the Birmingham system were open to abuse. This may have been because the system was administered with comparative benevolence. Despite this, the report undoubtedly stirred the guardians to greater efforts to reduce the overall cost of relief.

Conclusion

Ultimately it was almost twenty years before the 1834 Act was fully implemented. The on-going protests, along with the cost of building new workhouses, meant that in reality, outdoor relief continued. As time passed, however, the stigma attached to claiming relief increased meaning that ultimately fewer applied for it.

This information was gathered as part of the research for the Ambition & Destiny series. Click here to find out more.

References:

- BBC.co.uk/history/british/victorians

- Victorianweb.org/history/poorlaw

- Nadinemuller.org.uk/research/the-widow-and-the-law/

- Women and the Poor Law in Victorian and Edwardian England