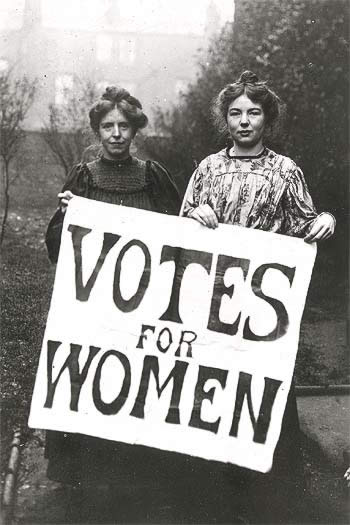

Early Women’s Suffrage

When people think of the women’s suffrage movement in the UK many think of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU, also known as the Suffragettes). This was the group that undertook the militant protests under the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst.

In fact, the women’s suffragette movement was only founded in 1903 at the start of the 20th century. By this time, women had become angry at the lack of progress being made by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage (NUWS). This was a movement set up in 1897 by Millicent Fawcett. In contrast to the WSPU, the NUWS believed that the way to secure the vote was through non-violent protest. They believed that if women caused trouble it would confirm to men they could not be trusted. The lack of progress with this approach, however, convinced the WSPU that more drastic action was required.

Although these bodies became established at the turn of the twentieth century, the suffrage movement had been active for many years prior to this. In the early years, campaigners were known as suffragists. The term suffragette came into being to describe those who used violent protest, although the term is now widely misused.

The First Great Battle of the Sexes

Initially, the suffrage campaign was closely associated with a sex war between men and women. Women started to rebel against historical male sexual domination. They campaigned against being forced into a sexual identity through the withholding of education and the right to vote. Many were not prepared to be defined by their biology and longed to be rid of the separate sphere ideology that left them powerless.

As far back as 1825 William Thompson and Anna Wheeler wrote an article entitled: An Appeal of One Half the Human Race, Women, Against the Pretensions of the Other Half, Men, to Retain Them in Political, and Thence in Civil and Domestic Slavery. This was in reply to an article that stated:

‘…women did not need the vote because their interests were the same as that of their fathers or husbands, who did have the vote.’

In subsequent years, individual acts of petition were taken to the government and local groups were established. This included the Sheffield Female Political Association who submitted a petition (unsuccessfully) to the House of Lords in 1851 calling for women’s suffrage.

By 1868, a number of local groups came together with the founding of the National Society for Women’s Suffrage (NSWS). This was the first attempt to create a unified voice for women’s suffrage, but due to splits in the membership, it was relatively ineffective.

Submission: A Woman’s Most Potent Charm

The hurdles the women faced were captured by the editor of The Times in 1868 when he wrote:

‘No woman has yet pretended to be on a level with men in physical strength. The fact is that physical strength has a good deal to do with politics in innumerable ways, and, for that reason alone, women are not capable of holding their own in the rough contests of the world. If they attempted to do it, they would sacrifice that delicacy, that gentleness, that submission that are now their most potent charms. They have at present the privileges and the protection of the weak. Let them undertake to defend themselves, and they must be content with the bare rights they can enforce. Instead of gaining any additional rights, they would risk some of the rights they possess; and they would inevitably lose the peculiar influence which is now derived from their very subordination.’

Between 1870 and 1880 the suffrage movement began to gain momentum and meetings were set up all over Britain. Speakers such as Millicent Fawcett and Mrs Ronniger attended meetings. During the 1870’s an average of 200,000 signatures a year were collected in support of votes for women.

Due to the lobbying of women and their supporters, the subject was debated in the House of Commons every year (excluding 1874) from 1870-1879. The debates continued beyond this time, although with less frequency. From 1886 onwards every vote taken showed that the majority of MPs favoured women’s suffrage. In spite of this, it was still not permitted to become law.

We Are Not Amused

Although it may be thought that having a female monarch would aid the women’s movement, it is clear they did not have royal support. In a private letter of 1870, when she learned that Viscountess Amberley had become president of the Bristol and West of England Women’s Suffrage Society, Queen Victoria wrote:

‘I am most anxious to enlist everyone who can speak or write to join in checking this mad, wicked folly of “Women’s Rights”, with all its attendant horrors, on which her poor feeble sex is bent, forgetting every sense of womanly feeling and propriety. Lady Amberley ought to get a good whipping. Were woman to unsex themselves by claiming equality with men, they would become the most hateful, heathen and disgusting of beings and would surely perish without male protection.”

Women are Meant to be Subordinate To Men

There were many arguments, often contradictory, made for and against granting women the vote. Many seem ludicrous by today’s standards but they were argued with vigour and full belief. Arguments against women’s suffrage included:

- Women are by nature and also according to God and the Bible meant to be subordinated to men

- Politics was none of women’s business; they knew nothing, and indeed should know nothing, about it

- Women are – or should be – far too busy with their home and community duties to take part in politics

- Women are too dainty and delicate for the rough and tumble of politics

- Men are made for public life; women for private

- It was a Trojan Horse: if you let them vote then soon they’d demand to become MPs, which, it was self-evident, would be absurd

- Anyone can get up a petition and get ignorant women to sign it

- Only people who could fight in war ought to have the vote, and women clearly could not

- Women of all classes are already represented in parliament via the votes cast by the men in their family

- Women already had a huge amount of influence over men, and therefore over parliament; giving them the vote gave them too much power

- Only men should legislate for women because only men know what is good for women

- Women have no grievances, or if they have, these can be put right by men

- Women’s interests in parliament are already protected by men

- Women would be hardened and sullied by politics, would become manly and unfeminine

- Women would be over-excited by politics and would have nervous breakdowns

- As a married woman had taken a vow to obey, giving her a vote amounted to giving her husband two votes

- Women are Conservative by nature, and the Liberals would lose the next election (said by Liberals)

- Votes for women will lead inevitably to socialism (said by Conservatives)

- Votes for women would merely enfranchise even more of the propertied classes (said by Labour party)

- Men are logical, stable, thoughtful and strong-minded; women are ornamental, quick-tempered, illogical, fickle and emotional

- If women cease to be under men’s protection they would be in competition with men and, being weaker, they would be oppressed and eventually go under

- If women had votes they would outnumber male voters, parliament would become feminised and Britain the laughing stock of the world

Sixty Years to See the First Signs of Success

Support for women’s suffrage increased over the years to the point where it was backed by the majority of MPs. Despite this, the Liberal government of 1901-1914 would not countenance the vote. This led to the militancy associated with the suffragette movement. Many have argued that this actually slowed down the granting of voting rights. Indeed it has been said that it was the First World War that led to women getting the vote. It changed the social and political landscape and with women actively working to support the war effort, there was a groundswell of opinion to grant them the vote.

Finally, in 1918, an act was passed giving women over the age of 30 the vote. This was a step in the right direction. It wasn’t until 1928, 60 years after campaigning began, that parliament finally equalised the voting age between men and women.

For the full list of arguments for and against female suffrage and further details on the subject, click here https://www.suffrageresources.org.uk/resource/3224/parliament-and-the-suffrage-movement

This information was gathered as part of the research for the Ambition & Destiny series. Click here to find out more.

Back to The Victorian Era